“The Machu Picchu of Azerbaijan.” That is how some locals have described the site of Alinja Castle, whose recently restored ruins are likely to become one of the prime tourist attractions of Azerbaijan’s disconnected Nakhchivan exclave.

The comparison has some merit. Like the Peruvian site, it sits way up an inaccessible peak and is distinctive for its various layers and stunning panoramic views. But its setting is on a stark crag rather than a lush green South American mountain. And unlike Machu Picchu you might have the whole place to yourself as I did in March 2016.

There was probably a fortress here over two millennia ago and the site has witnessed many fearsome battles, yet till recently there was little more than a handful of inaccessible stones to show for all that. So its recent restoration has been a gargantuan task. After all, the fortress’s raison d’être was invincibility and until the construction of some 1600 steps, getting anywhere near the top was by a dangerously steep and slithery trail that took great concentration and surefootedness. Now there’s a copper-effect handrail and some bench seats half way up at which to rest, but reaching the main site still took me a good 45 minutes’ panting and a fair degree of physical exertion. As I climbed, I imagined the terror such an ascent must have held for attacking medieval soldiers dressed in heavy chainmail, scrambling up sword-in-hand while defenders threw down endless cascades of rocks.

At least seven theories exist for the etymology of the name Alinja. The one of it being a Mongol tribe is definitively wrong I was assured by Ismayil Hajiev, chairman of the Nakhchivan Academy of Sciences and author of a massive three-volume history of the exclave. It can’t be true because Alinja (or its variants Alinjak, Elinjak, Yernjak, etc) were mentioned in the epic of Dede Qorqud which was written much earlier. Other ideas include some reference to a son of Noah, an archaic word meaning ‘invincible’ or, most likely according to Hajiyev, from the ancient Elinjak tribe. Though a small oasis village today, Alinja town was at one time one of Nakhchivan’s major population centres and minted its own coinage. The dramatically beautiful location, a valley tucked into a protective horseshoe of soaring crags directly behind Alinja Castle, would have had obvious appeal for a medieval urban site.

Alinja and the Atabeys

The site has witnessed many dramatic historical events including a 914 AD siege that culminated in the ceremonial torturing and beheading of upstart King Smbat I to ‘encourage’ the castle’s capitulation to the local Sajid dynasty. But it grew to particular importance in the 12th century under the Atabeys (Atabeks). Under the post-Mongol Seljuk Empire (covering much of the Middle East and west Asia), an Atabey or Atabek had been the title for a regional governor. However, as the Seljuk Empire imploded, regions suddenly gained considerable autonomy and several went on to found what were essentially their own statelets. A particularly important Atabey regime based initially at Ganja and then at Nakhchivan was the Eldiguzid dynasty founded by Shamseddin Eldeniz.

Eldeniz had started life as the slave of a prominent Seljuk minister yet somehow worked his way up, was appointed ruler of Arran and Azerbaijan and eventually married the widow of Seljuk Sultan Toghrul II. It was perhaps this wife that thus deserves credit for the golden age that blossomed briefly in Nakhchivan in this era. Remembered simply as Momine Khatun, meaning ‘Pious Lady’ rather than being a personal name, she rather than Eldeniz is commemorated by the splendidly faceted mausoleum in Nakhchivan City that remains Azerbaijan’s most beautiful medieval monument. By the time the tomb tower was finished, Eldeniz had long been buried himself and replaced as ruler by his son Jahan Pehlavan whose reputedly superhuman strength meant he could unbend horseshoes with his bare hands, throw cows across fences and bend a whole stack of metal trays. In 1175 Palavan moved his capital to Hamadan (now in Iran) but initially he left a treasury at Alinja where his second wife, Zahida, remained in residence.

Fifty years later, it was to Alinja (via Ganja) that the last Atabey ruler, Ozbek, retreated in the face of dual attacks. First the Mongols had hit Nakhchivan in 1221, then the forces of the central Asian state of Khwarazm arrived having themselves been displaced by Mongol attacks. The Khwarazm leader, Jalal-addin Mingburnu, seized Tabriz in June 1225 and with it Ozbek’s wife, Maleyka Khatun, who had been a daughter of the last Seljuk Sultan. According to folk myth, Maleyka later divorced Ozbek on hearing that he had executed one of her favourite slaves. And then to add insult to injury, she married her captor Jalal-addin in Khoy. How much choice she had in the matter remains open to much debate, but reputedly on hearing the news of his wife’s betrayal, Ozbek dropped dead with chagrin. And with Ozbek’s death the Atabey dynasty essentially ceased to exist, his one son being deaf and dumb and thus unable to fit the macho needs of a medieval ruler. But Alinja’s greatest footnote in history was yet to come.

Timur’s Tussles

In the later 13th and early 14th centuries, Alinja and Nakhchivan fell within the Elkhanid/Ilkhanate Mongol-Iranian empire. This divided around 1335 into a matrix of mutually antagonistic sub-dynasties, notably the Jalayirids based at Baghdad fighting the Tabriz-based Chobanids and later the Qara Qoyunlu Turkmens, their erstwhile subordinates. After years of infighting between such factions, the arrival of Timur’s (Tamerlane) forces from Central Asia added yet further complexity. Over a period of 14 years, Alinja Castle (1387-1401) was thereupon subjected to a whole series of sieges by the armies of Timur and his son Miranshah. An episode from this rolling conflict is depicted in one of Nakhchivan City History Museum’s most eye-catching exhibits, a magnificent painting by Torgrul Narimanbeyov. In that wild 2.8m canvas, the Alinja crag is rendered with expressively waving brush strokes making the mountain look somewhere between a Van Gogh cypress tree and a failed hipster’s quiff.

The castle’s one historic weakness was the lack of a permanent summer water supply as the spring near the western entrance gate was comparatively vulnerable and liable to dry up in certain seasons. To compensate, a series of rainwater collecting pools were fed by an ingenious series of aryks – carved guttering etched into the living rock to redirect runoff. Several pools and aryks can still be clearly seen as you explore the site. The system proved remarkably effective but did leave the castle prone to trouble if drought and siege should occur together. That was almost the case during the Timur-era attacks. At one point, increasingly thirsty defenders were about to give up when, the night before capitulating, a torrential downpour engulfed the area leaving the attackers sodden and the defenders with fully replenished drinking water.

In 1393, Timur’s overwhelmingly superior army did manage to get within the first level of fortifications while the main defensive force led by a certain Emir Altun were away attempting to plunder Tabriz. But somehow Altun managed to return, turn the tables and massacre a phenomenal 20,000 of Timur’s troops. A new siege was started soon after but relieved in 1398-9 by a Georgian/Albanian army sent from Sheki led by one of the sons of Jalayirid Sultan Ahmad (aka Hamidus) who, according to some versions of the tale, had taken refuge in Alinja. Timur (or at least his son, Miranshah) only finally proved successful in snatching Alinja castle during 1401, whether through treachery or because the castle had been essentially abandoned by its defenders (sources differ).

Three years later Henry III of Castillo/Spain’s ambassador Ruy González de Clavijo passed by the site (2nd June 1404) en route to his appointment with Timur’s court. Clavijo observed:

on the left hand side of the ‘road’ [was a place], called Alinga, which was on a high mountain, and surrounded by a wall with towers within which there were many vineyards, and fruit gardens, and corn fields, and streams, and pastures for sheep, and on the highest part of the mountain there was a castle.

This either suggests a remarkably swift recovery or underlines that the final siege had not been quite as destructive as one imagines.

The Jalayirids were thereafter eclipsed by their erstwhile subjects, the Qara Qoyunlu who stormed through Azerbaijan and Iraq after Timur’s death in 1405. The Qara Qoyunlu leader after 1420, Qara Iskander, continued an ongoing joust with Timurid forces, led by Timur’s son Shahrokh Mirza (aka Shah Rukh) and with his own brothers Abu Said (who he executed) and Jahan Shah who finally besieged Iskander in yet another battle at Alinja. As ever the fortress proved invincible, but in a woeful culmination to the family saga, Iskander was eventually murdered by his own son Shah Kubad.

The Site Today

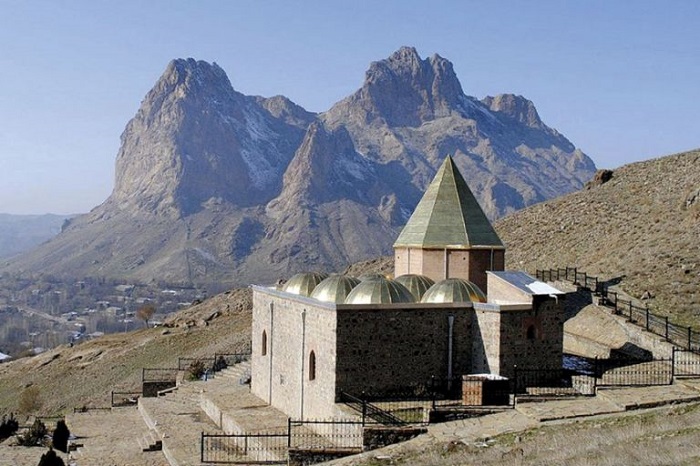

Despite the many tales of blood and internecine feuds, what attracts visitors today is the sense of peace and tranquillity. Probably the most spectacular time to be at the top is around sunset when sunbeams pierce the clouds and shower their magic across the undulating peaks, valleys and reservoir lakes that are laid out way below. And evening light has the added bonus of bringing a golden-red blush to the abrupt rocky tooth of Mt Ilan Dagh whose grooved summit is said to have had its conspicuous notch chipped out of it by Noah’s Ark. The Ilan Dagh views are hidden from many angles but easily spied from the castle’s western tip. The crag should also be visible from the higher, Shahtakhti, section of the fortress which was once the royal residence section, but that is as yet unreconstructed and reaching it is currently a dangerous scramble.

The main castle site has three levels, of which the central one is laid out in what looks almost like a French formal garden albeit using walls rather than topiary. A central courtyard is surrounded by head-high, roofless ‘rooms’ which are empty and seek only to give a sense of the space rather than actually containing any exhibits. The walls are of bare local stone and the lack of anything more fanciful is something of a relief in comparison to the heavy-handed reconstruction of Nakhchivangala – the supposedly ancient citadel of Nakhchivan whose extensive 21st century reincarnation with central domed museum evokes little of any historical atmosphere.

Mark Elliott is the author of the popular guidebook Azerbaijan with Excursions to Georgia whose 5th edition is currently in preparation.

Source: Visions of Azerbaijan magazine